Okay, so to recap, here at the Kennedy School of Government I’m interested in the social, economic and policy changes brought about by the way digital technologies expand or threaten how we can solve problems, relate to one another, and reimagine institutions and the world.

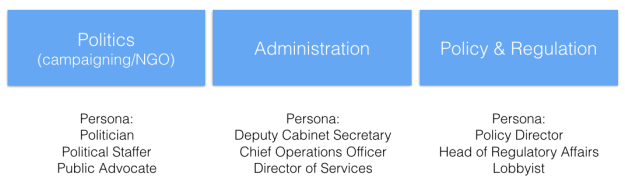

We have a range of students who fall into three broad camps:

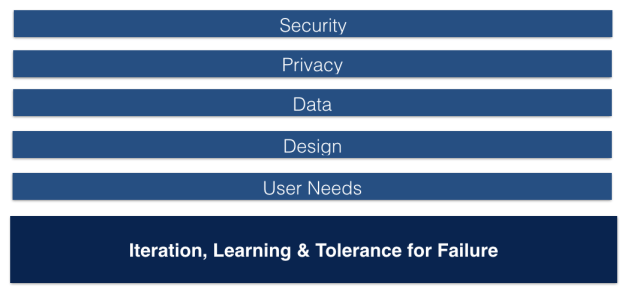

To whom we are focused on teaching a culture of learning as well as a number of key foundational topics and skills:

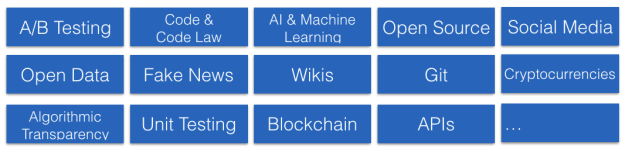

To help them grasp a wide range of concepts, processes and tools made possible by digital technology:

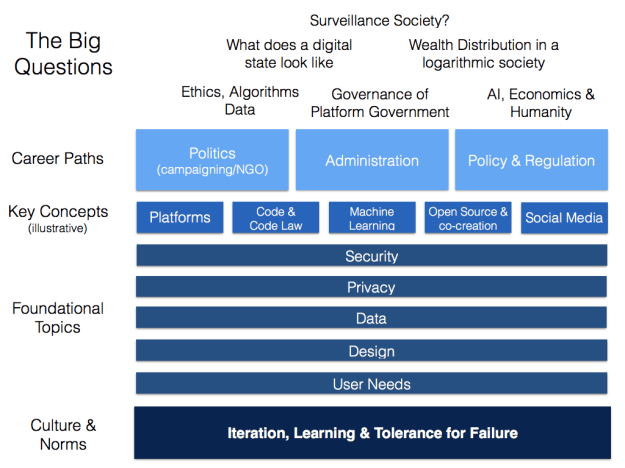

I combine those to provide a more general framework for how I think about teaching digital at a policy school that looks like this.

One element I like about this chart is that it identifies some shared learning areas of which students should have a solid understanding. This enables one to concentrate resources in one or more core courses that provide students with basic building blocks of knowledge that can be used to learn and be critical about a range of concepts and ideas.

It also allows us to create a set of courses that each dive deeper into each of the foundational topics and related concepts secure in the knowledge that such courses will be useful to a broad range of students. Examples of these courses include Bruce Schneier’s class on security, Jim Waldo’s class on privacy and Dana Chisnell’s class on design thinking.

This approach also allows for flexibility. As I mentioned in an earlier post, depending on their career paths students may invest more heavily in some foundational topics. A regulator may be more concerned with privacy, design and data while a cyber security expert may be more interested in security and data. Thus students can opt to dive deeper into areas they think will be critical to their career. Nonetheless, my sense is that regardless of role, a basic understanding of each of the above foundational topics (as well as the underlying culture and norms of iteration and learning) will serve them well in any role and so getting an overview of each is critical.

With more students having been exposed to a range of the foundational topics I also feel more comfortable offering courses that focus on some of the concepts. Again it is worth noting that the “concepts” part of the chart encapsulates thousands of possible issues. Not only are there far more than can be taught, but they are in constant flux. Some fall out of favor or become obsolete while new ones are constantly emerging. That said, some are likely essential to everyone (for example, I teach all my students about the concept of a platform) and others are likely to be important to specific roles, indeed part of the function of a school and a teacher is to figure out which of these concepts — for a given role — are essential versus merely good to know versus unnecessary. A great example of this type of course includes Nicco Mele’s course on technology and the media and his course on technology and political campaigns.

I’ll talk more about how we map out classes in a subsequent post.

The Big Questions

Part of the goal for a policy school is to educate and train students, equipping them with the skills and knowledge they need to be successful in creating public value and engage public organizations in digital transformation.

But as a school of public policy and, frankly one that has a global reach, we have a responsibility to also ask bigger questions. One hope I have is to push the school to understand how some of the questions that are asked in the “digital” sphere are in reality Big Questions that affect society at large, the fabric of democracy and governance, the nature of human rights, etc… and need the engagement of the school at large focused on them. This is not to say that these questions are the only questions that matter. Climate change, massive inequality, and managing the US-China relationship probably represent the great challenges, if not in some cases, the existential threats of our time, and deserve much attention. But there are questions created by issues in the digital sphere that are similar in nature.

These include:

- Have we become a surveillance society? With both the state and companies tracking our every move, what does this mean for freedom? For dissent? For citizenship?

- If the 20th century was about harnessing the power of the state to reshape the distribution of wealth under capitalism from a power law into a bell curve, how will we do the same in the internet age?

- What does an API-driven government look like? What will be the checks and balances around power, surveillance, and privacy in such an institution?

- Will artificial intelligence and the second machine age leave (almost) everyone unemployed? And if they do, what then?

I see these and other questions like them as core to the role and purpose of a policy school. They may not be the questions that all, or even most of our students are required to ask day to day in the jobs they take up, but they are the questions that we all, as citizens, need to start wrestling with as we think about what we want the future of our world to look like.

Okay, I’ll stop there. More to come soon.

This is the sixth in a series of pieces about how I’m wrestling with how to teach about digital technologies at policy schools. If you’re interested you can read:

- part one: Why Digital Matters

- part two: Defining Digital

- part three: Our Users and What They Need

- part four: The Trap — Teaching Tech and Concepts

- part five: Foundational Topics

- part six: Bringing it Together (this post)