Backdrop

On Friday the Canadian Government released its draft national action plan. Although not mentioned overtly in the document, these plans are mandated by the Open Government Partnership (OGP), in which member countries must draft National Action Plans every two years where they lay out tangible goals.

I’ve both written reviews about these plans before and offered suggestions about what should be in them. So this is not my first rodeo, nor is it for the people drafting them.

Purpose of this piece

In the very niche world of open government there are basically two types of people. Those who know about the OGP and Canada’s participation (hello 0.01%!), and those who don’t (hello overwhelming majority of people — excited you are reading this).

If you are a journalist, parliamentarian, hill staffer, academic, public servant, consultant, vendor, or everyday interested citizen already following this topic, here are thoughts and ideas to help shape your criticisms and/or focus your support and advice to government. If you are new to this world, this post can provide context about the work the Canadian Government is doing around transparency to help facilitate your entrance into this world. I’ll be succinct — as the plan is long, and your time is finite.

That said, if you want more details about thoughts, please email me — happy to share more.

The Good

First off, there is lots of good in the plan. The level of ambition is quite high, a number of notable past problems have been engaged, and the goals are tangible.

While there are worries about wording, there are nonetheless a ton of things that have been prioritized in the document that both myself and many people in the community have sought to be included in past plans. Please note, that “prioritized” is distinct from “this is the right approach/answer.” Among these are:

- Opening up the Access to Information Act so we can update it for the 21st century. (Commitment 1)

- Providing stronger guarantees that Government scientists — and the content they produce — is made available to the public, including access to reporters (Commitment 14)

- Finding ways to bake transparency and openness more firmly into the culture and processes of the public service (Commitment 6 and Commitment 7)

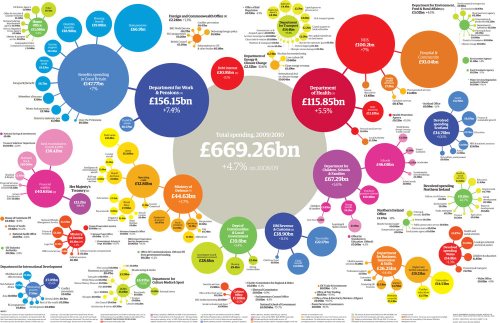

- Ensuring better access to budget and fiscal data (Commitment 9, Commitment 10 and Commitment 11)

- Coordinating different levels of government around common data standards to enable Canadians to better compare information across jurisdictions (Commitment 16)

- In addition, the publishing of Mandate Letters (something that was part of the Ontario Open by Default report I helped co-author) is a great step. If nothing else, it helps public servants understand how to better steer their work. And the establishment of Cabinet Committee on Open Government is worth watching.

Lots of people, including myself, will find things to nit pick about the above. And it is always nice to remember:

a) It is great to have a plan we can hold the government accountable to, it is better than the alternative of no plan

b) I don’t envy the people working on this plan. There is a great deal to do, and not a lot of time. We should find ways to be constructive, even when being critical

Three Big Ideas the Plan Gets Right

Encouragingly, there are three ideas that run across several commitments in the plan that feel thematically right.

Changing Norms and Rules

For many of the commitments, the plan seeks to not simply get tactical wins but find ways to bake changes into the fabric of how things get done. Unlike previous plans, one reads a real intent to shift culture and make changes that are permanent and sustainable.

Executing on this is exceedingly difficult. Changing culture is both hard to achieve and measure. And implementing reforms that are difficult or impossible to reverse is no cake walk either, but the document suggests the intent is there. I hope we can all find ways to support that.

User Centric

While I’m not a fan of all the metrics of success, there is a clear focus on making life easier for citizens and users. Many of the goals have an underlying interest of creating simplicity for users (e.g. a single place to find “x” or “y”). This matters. An effective government is one that meets the needs of its citizens. Figuring out how to make things accessible and desirable to use, particularly with information technology, has not been a strength of governments in the past. This emphasis is encouraging.

There is also intriguing talk of a “Client-First” service strategy… More on that below.

Data Standards

There is lots of focus on data standards. Data standards matter because it is hard to use data — particularly across government, or from different governments and organizations — if they have different standards. Imagine trying if every airline used a different standard to their tickets, so to book a trip involving more than one airline would be impossible as their computers wouldn’t be able to share information with one another, or you. That challenging scenario is what government looks like today. So finding standards can help make government more legible.

So seeing efforts like piloting the Open Contracting Data Standard in Commitment 9, getting provincial and local governments to harmonize data with the feds in Commitment 16 and “Support Openness and Transparency Initiatives around the World” in Commitment Commitment 18 are nice…

… and it also makes it glaring when it is not there. Commitment 17 — Implement the Extractives Sector Transparency Measures Act — is still silent about implementing the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative standard and so feels inconsistent with the other commitments. More on this below.

The Big Concerns

While there are some good themes, there are also some concerning ones. Three in particular stand out:

Right Goal, Wrong Strategy

At the risk of alienating some colleagues, I’m worried about the number of goals that are about transparency for transparency’s sake. While I’m broadly in favour of such goals… they often risk leading nowhere.

I’d much rather see specific problems the government wants to focus its resources on open data or sharing scientific materials on. When no focus is defined and the goal is to just “make things transparent” what tends to get made transparent is what’s easy, not what’s important.

So several commitments, like numbers 3, 13, 14, 15, essentially say “we are going to put more data sets or more information on our portals.” I’m not opposed to this… but I’m not sure it will build support and alignment because doing that won’t be shaped to help people solve today’s problems.

A worse recommendation in this vein is “establish a national network of open data users within industry to collaborate on the development of standards and practices in support of data commercialization.” There is nothing that will hold these people together. People don’t come together to create open data standards, they come together to solve a problem. So don’t congregate open data users — they have nothing in common — this is like congregating “readers.” They may all read, but their expertise will span a wide variety of interests. Bring people together around a problem and then get focused on the data that will help them solve it.

To get really tangible, on Friday the Prime Minister had a round table with local housing experts in Vancouver. One outcome of that meeting might have been the Prime Minister stating, “this is a big priority, I’m going to task someone with finding all the data the federal government has that is relevant to this area so that all involved have the most up to date and relevant information we can provide to improve all our analyses.”

Now maybe the feds have no interesting data on this topic. Maybe they do. Maybe this is one of the PMOs top 6 priorities, maybe it isn’t. Regardless, the government should pick 3–8 policy areas they care deeply about and focus sharing data and information on those. Not to the exclusion of others, but to provide some focus. Both to public servants internally, so they can focus their efforts, and to the public. That way, experts, the public and anyone can, if they are able, grab the data to help contribute to the public discourse on the topic.

There is one place where the plan comes close to taking this approach, in Commitment 22: Engage Canadians to Improve Key Canada Revenue Agency Services. It talks a lot about public consultations to engage on charitable giving, tax data, and improving access to benefits. This section identifies some relatively specific problem the government wants to solve. If the government said it was going to disclose all data it could around these problems and work with stakeholders to help develop new research and analysis… then they would have nailed it.

Approaches like those suggested above might result in new and innovative policy solutions from both traditional and non-traditional sources. But equally important, such an approach to a “transparency” effort will have more weight from Ministers and the PMO behind it, rather than just the OGP plan. It might also show governments how transparency — while always a source of challenges— is also a tool that can help advance their agenda by promoting conversations and providing feedback. Above all it would create some models, initially well supported politically, that could then be scaled to other areas.

Funding

I’m not sure if I read this correctly but the funding, with $11.5M in additional funds over 5 years (or is that the total funding?) is feeling like not a ton to work with given all the commitments. I suspect many of the commitments have their own funding in various departments… but it makes it hard to assess how much support there is for everything in the plan.

Architecture

This is pretty nerdy… but there are several points in the plan where it talks about “a single online window” or “single, common search tool.” This is a real grey area. There are times when a single access point is truly transformative… it creates a user experience that is intuitive and easy. And then there are times when a single online window is a Yahoo! portal when what you really want is to just go to google and do your search.

The point to this work is the assumption that the main problem to access is that things can’t be found. So far, however, I’d say that’s an assumption, I’d prefer the government test that assumption before making it a plan. Why Because a LOT of resources can be expended creating “single online windows.”

I mean, if all these recommendations are just about creating common schemas that allow multiple data sources to be accessed by a single search tool then… good? (I mean please provide the schema and API as well so others can create their own search engines). But if this involves merging databases and doing lots of backend work… ugh, we are in for a heap of pain. And if we are in for a heap of pain… it better be because we are solving a real need, not an imaginary one.

The Bad

There are a few things that I think have many people nervous.

Access to Information Act Review

While there is lots of good in that section, there is also some troubling language. Such as:

- A lot of people will be worried about the $5 billing fee for FOIA requests. If you are requesting a number of documents, this could represent a real barrier. I also think it creates the wrong incentives. Governments should be procuring systems and designing processes that make sharing documents frictionless — this implies that costs are okay and that there should be friction in performing this task.

- The fact that Government institutions can determine a FOIA request is “frivolous” or “vexatious” so can thus be denied. Very worried about the language here.

- I’m definitely worried about having mandatory legislative review of the Access to Information Act every five years. I’d rather get it right once every 15–30 years and have it locked in stone than give governments a regular opportunity to tinker with and dilute it.

Commitment 12: Improve Public Information on Canadian Corporations

Having a common place for looking up information about Canadian Corporations is good… However, there is nothing in this about making available the trustees or… more importantly… the beneficial owners. The Economist still has the best article about why this matters.

Commitment 14: Increase Openness of Federal Science Activities (Open Science)

Please don’t call it “open” science. Science, by definition, is open. If others can’t see the results or have enough information to replicate the experiment, then it isn’t science. Thus, there is no such thing as “open” vs. “closed” science. There is just science, and something else. Maybe it’s called alchemy or bullshit. I don’t know. But don’t succumb to the open science wording because we lose a much bigger battle when you do.

It’s a small thing. But it matters.

Commitment 15: Stimulate Innovation through Canada’s Open Data Exchange (ODX)

I already talked about about how I think bringing together “open data” users is a big mistake. Again, I’d focus on problems, and congregate people around those.

I also suspect that incubating 15 new data-driven companies by June 2018 is not a good idea. I’m not persuaded that there are open data businesses, just businesses that, by chance, use open data.

Commitment 17: Implement the Extractives Sector Transparency Measures Act

If the Extractives Sector Transparency Measures Act is that same as it was before then… this whole section is a gong show. Again, no EITI standard in this. Worse, the act doesn’t require extractive industries to publish payments to foreign governments in a common standard (so it will be a nightmare to do analysis across companies or industry wide). Nor does it require that companies submit their information to a central repository, so aggregating the data about the industry will be nigh high impossible (you’ll have to search across hundreds of websites).

So this recommendation: “Establish processes for reporting entities to publish their reports and create means for the public to access the reports” is fairly infuriating as it a terrible non-solution to a problem in the legislation.

Maybe the legislation has been fixed. But I don’t think so.

The Missing

Not in the plan is any reference to the use of open source software or shares that software across jurisdictions. I’ve heard rumours of some very interesting efforts of sharing software between Ontario and the federal government that potentially saves tax payers millions of dollars. In addition, by making the software code open, the government could employ security bug bounties to try to make it more secure. Lots of opportunity here.

The Intriguing

The one thing that really caught my eye, however, was this (I mentioned it earlier):

The government is developing a Service Strategy that will transform service design and delivery across the public service, putting clients at the centre.

Now that is SUPER interesting. A “Service Strategy”? Does this mean something like the Government Digital Service in the UK? Because that would require some real resources. Done right it wouldn’t just be about improving how people get services, but a rethink of how government organizes services and service data. Very exciting. Watch that space.