Over at the Programmable City website Rob Kitchin has a thoughtful blog post on open data critiques. It is very much worth reading and wider discussion. Specifically, there are two competing things worth noting. First, it is important for the open data community – and advocates in particular – to acknowledge the responsibility we have in debates about open data. Second, I’d like to examine some of the critiques raised and discuss those I think misfire and those that deserve deeper dives.

Open Data as Dominant Discourse

During my 2011 keynote at Open Government Data camp I talked about how the open data movement was at an inflection point:

For years we have been on the outside, yelling that open data matters. But now we are being invited inside.

Two years later the transition is more than complete. If you have any doubts, consider this picture: Once you have these people talking about things like a G8 Open Data Charter you are no longer on the fringes. Not even remotely.

Once you have these people talking about things like a G8 Open Data Charter you are no longer on the fringes. Not even remotely.

It also means understanding the challenges around open data has never been more important. We – open data advocates – are now complicit it what many of the above (mostly) men decide to do around open data. Hence the importance of Rob’s post. Previously those with power were dismissive of open data – you had to scream to get their attention. Today, those same actors want to act now and go far. Point them (or the institutions they represent) in the wrong direction and/or frame an issue incorrectly and you could have a serious problem on your hands. Consequently, the responsibility of advocates has never been greater. This is even more the case as open data has spread. Local variations matter. What works in Vancouver may not always be appropriate in Nairobi or London.

I shouldn’t have to say this but I will, because it matters so much: Read the critiques. They matter. They will make you better, smarter, and above all, more responsible.

The Four Critiques – a break down

Reading the critiques and agreeing with them is, of course, not the same thing. Rob cites four critiques of open data: funding and sustainability, politics of the benign and empowering the empowered, utility and usability, and neoliberalisation and marketisation of public services. Some of these I think miss the real concerns and risks around open data, others represent genuine concerns that everyone should have at the forefront of their thinking. Let me briefly touch on each one.

Funding and sustainability

This one strikes me as the least effective criticism. Outside the World Bank I’ve not heard of many examples where government effectively sell their data to make money. I would be very interested in examples to the contrary – it would make for a great list and would enlighten the discussion – although not, I suspect in ways that would make either side of the discussion happy.

The little research that has been done into this subject has suggested that charging for government data almost never yields much money, and often actually serves as a loss creating mechanism. Indeed a 2001 KPMG study of Canadian geospatial data found government almost never made money from data sales if purchases by other levels of government were not included. Again in Canada, Statistics Canada argued for years that it couldn’t “afford” to make its data open (free) as it needed the revenue. However, it turned out that the annual sum generated by these sales was around $2M dollars. This is hardly a major contributor to its bottom line. And of course, this does not count the money that had to go towards salaries and systems for tracking buyers and users, chasing down invoices, etc…

The disappointing line in the critique however was this:

de Vries et al. (2011) reported that the average apps developer made only $3,000 per year from apps sales, with 80 percent of paid Android apps being downloaded fewer than 100 times. In addition, they noted that even successful apps, such as MyCityWay which had been downloaded 40 million times, were not yet generating profits.

Ugh. First, apps are not what is going to make open data interesting or sexy. I suspect they will make up maybe 5% of the ecosystem. The real value is going to be in analysis and enhancing other services. It may also be in the costs it eliminates (and thus capital and time it frees up, not in the companies it creates), something I outlined in Don’t Measure the Growth, Measure the Destruction.

Moreover, this is the internet. The average doesn’t mean anything. The average webpage probably gets 2 page views per day. That hardly means there aren’t lots of very successful webpages. The distribution is not a bell curve, its a long tail, so it is hard to see what the average tells us other than the cost of experimentation is very, very low. It tells us very little about if there are, or will be successful uses of open data.

Politics of the benign and empowering the empowered

The is the most important critique and it needs to be engaged. There are definitely cases where data can serve to further marginalize at risk communities. In addition, there are data sets that for reasons of security and privacy, should not be made open. I’m not interested in publishing the locations of women’s shelters or worse, the list of families taking refuge in them. Nor do I believe that open data will always serve to challenge the status quo or create greater equality. Even at its most reductionist – if one believes that information is power, then greater ability to access and make us of information makes one more powerful – this means that winners and losers will be created by the creation of new information.

There are however, two things that give me some hope in this space. The first is that, when it comes to open data, the axis of competition among providers usually centers around accessibility. For example, the Socrata platform (an provider of open data portals to government) invests heavily in creating tools that make government data accessible and usable to the broadest possible audience. This is not a claim that all communities are being engaged (far from it) and that a great deal more work cannot be done, but there is a desire to show greater use which drives some data providers to try to find ways to engage new communities.

The second is that if we want to create data literate society – and I think we do, for reasons of good citizenship, social justice and economic competitiveness – you need the data first for people to learn and play with. One of my most popular blog posts is Learning from Libraries: The Literacy Challenge of Open Data in which I point out that one of the best ways to help people become data literate is to give them more interesting data to play with. My point is that we didn’t build libraries after everyone knew how to read, we built them beforehand with the goal of having them as a place that could facilitate learning and education. Of course libraries also often have strong teaching components to them, and we definitely need more of this. Figuring out who to engage, and how it can be done most effectively is something I’m deeply interested in.

There are also things that often depress me. I struggle to think of technologies that did not empower the empowered – at least initially. From the cell phone to the car to the printing press to open source software, all these inventions have had helped billions of people, but they did not distribute themselves evenly, especially at first. So the question cannot be reduced to – will open data empower the empowered, but to what degree, and where and with whom. I’ve seen plenty of evidence where data has enabled small groups of people to protect their communities or make more transparent the impact (or lack there of) of a government regulation. Open data expands the number of people who can use government information for their own ends – this, I believe is a good thing – but that does not mean we shouldn’t be constantly looking for ways to ensure that it does not reinforce structural inequity. Achieving perfect distribution of the benefits of a new technology, or even public policy, is almost impossible. So we cannot make perfect the enemy of the good. However, that does not hide the fact that there are real risk – and responsibilities as advocates – that need to be considered here. This is an issue that will need to be constantly engaged.

Utility and Usability

Some of the issues around usability I’ve addressed above in the accessibility piece – for some portals (that genuinely want users) the axis of evolution is pointed in the right direction with governments and companies (like Socrata) trying to embed more tools on the website to make the data more usable.

I also agree with the central concern (not a critique) of this section, which is that rather than creating a virtuous circle, poorly thought out and launched open data portals will create a negative “doomloops” in which poor quality data begets little interest which begets less data. However, the concern, in my mind, focuses on to narrow a problem.

One of the big reasons I’ve been an advocate of open data was a desire not just to help citizens, non-profits and companies gain access to information that could help them with their missions, but to change the way government deals with its data so that it can share it internally more effectively. I often cite a public servant I know who had a summer intern spend 3 weeks surfing the national statistical agency website to find data they knew existed but could not find because of terrible design and search. A poor open data site is not just a sign that the public can’t access or effectively use government data, it usually suggests that the governments employees can’t access or effectively use their own data. This is often deeply frustrating to many public servants.

Thus, the most important outcome created by the open data movement may have been making governments realize that data represents an asset class that of which they have had little understanding (outside, sadly, the intelligence sector, which has been all too aware of this) and little policy and governance (outside, say, the GIS space and some personal records categories). Getting governments to think about data as a platform (yes, I’m a fan of government as a platform for external use, but above all for internal use) is, in my mind, one way we can both enable public servants to get better access to information while simultaneously attacking the huge vendors (like SAP and Oracle) whose $100 million dollar implementations often silo off data, rarely produce the results promised and are so obnoxiously expensive it boggles the mind (Clay Johnson has some wonderful examples of the roughly 50% of large IT projects that fail).

They key to all this is that open data can’t be something you slap on top of a big IT stack. I try to explain this in It’s the Icing Not the Cake, another popular blog post about why Washington DC was able to effectively launch an open data program so quickly (which was, apparently, so effective at bringing transparency to procurement data the subsequent mayor rolled it back). The point is, that governments need to start thinking in terms of platforms if – over the long term – open data is going to work. And it needs to start thinking of itself as the primary consumer of the data that is being served on that platform. Steve Yegge’s brilliant and sharp witted rant on how Google doesn’t get platforms is an absolute must read in this regard for any government official – the good news is you are not alone in not finding this easy. Google struggles with it as well.

My main point. Let’s not play at the edges and merely define this challenge as one of usability. It is much, much bigger problem than that. It is a big, deep, culture-changing BHAG problem that needs tackling. If we get it wrong, then the big government vendors and he inertia of bureaucracy win. We get it right and we potentially could save taxpayers millions while enabling a more nimble, effective and responsive government.

Neoliberalisation and Marketisation of Government

If you not read Jo Bates article “Co-optation and contestation in the shaping of the UK’s Open Government Data Initiative” I highly recommend it. There are a number of arguments in the article I’m not sure I agree with (and feel are softened by her conclusion – so do read it all first). For example, the notion that open data has been co-opted into an “ideologically framed mould that champions the superiority of markets over social provision” strikes me as lacking nuance. One of the things open data can do is create a public recognition of a publicly held data set and the need to protect these against being privatized. Of course, what I suspect is that both things could be true simultaneously – there can be increased recognition of the importance of a public asset while also recognizing the increased social goods and market potential in leveraging said asset.

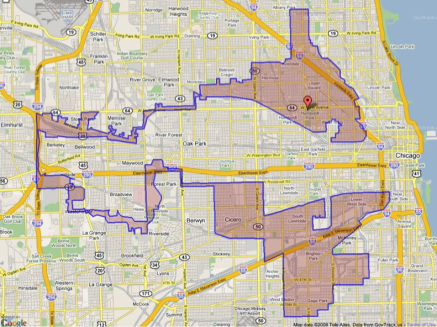

However, there is one thing Bates is absolutely correct about. Open data does not come into an empty playing field. It will be used by actors – on both the left and right – to advance their cause. So I too am uncomfortable with those that believe open data is going to somehow depoliticize government or politics – indeed I made a similar argument in a piece in Slate on the politics of data. As I try to point out you can only create a perverse, gerrymandered electoral district that looks like this…

… if you’ve got pretty good demographic data about target communities you want to engage (or avoid). Data – and even open data – doesn’t magically make things better. There are instances where open data can, I believe, create positive outcomes by shifting incentives in appropriate ways… but similarly, it can help all sorts of actors find ways to satisfy their own goals, which may not be aligned with your – or even society at large’s – goals.

… if you’ve got pretty good demographic data about target communities you want to engage (or avoid). Data – and even open data – doesn’t magically make things better. There are instances where open data can, I believe, create positive outcomes by shifting incentives in appropriate ways… but similarly, it can help all sorts of actors find ways to satisfy their own goals, which may not be aligned with your – or even society at large’s – goals.

This makes voices like Bates deeply important since they will challenge those of us interested in open data to be constantly evaluating the language we use, the coalitions we form and the priorities that get made, in ways that I think are profoundly important. Indeed, if you get to the end of Bates article there are a list of recommendations that I don’t think anyone I work with around open data would find objectionable, quite the opposite, they would agree are completely critical.

Summary

I’m so grateful to Rob for posting this piece. It is has helped me put into words some thoughts I’ve had, both about the open data criticisms as well as the important role the critiques play. I try hard to be critical advocate of open data – one who engages the risks and challenges posed by open data. I’m not perfect, and balancing these two goals – advocacy with a critical view – is not easy, but I hope this shines some window into the ways I’m trying to balance it and possible helps others do more of it as well.