After sharing the idea behind this post with Bruce Schneier, I’ve been encouraged to think a little more about what Werewolf can teach us about trust, security and rational choices in communities that are, or are at risk of, being infiltrated by a threat. I’m not a security expert, but I do spend a lot of time thinking about negotiation, collaboration and trust, and so thought I’d pen some thoughts. The more I write below, the more I feel Werewolf could be a fun teaching tool. This is something I hope we can do “research” on at Berkman next week.

For those unfamiliar with Werewolf (also known as mafia), it’s very simple:

At the start of the game each player is secretly assigned a role by a facilitator. Typically there are 3 werewolves (who make up one team) and around 15 villagers, including one seer and one healer (who make up the other team).

Each turn of the game has two alternating phases. The first phase is “night,” during which everyone covers their eyes. The facilitator then “wakes” the werewolves who agree on a single villager they “murder.” The werewolves then return to sleep. The seer “wakes” up and points at one sleeping player and the facilitator informs the seer if that that player is a werewolf or villager. The seer then goes back to sleep. Finally the healer “wakes” up and selects one person to “heal.” If that person was chosen to be murdered by the werewolves during the night they are saved and do not die.

The second phase is “day”; this starts with everyone “waking up” (uncovering their eyes). The facilitator identifies who has been murdered (assuming they were not healed). That person is immediately eliminated from the game. The surviving players – e.g. the remaining villagers and the werewolves hidden among them – then debate who among them is a werewolf. The “day” ends with a vote to eliminate a suspect (who is also immediately removed from the game).

Play continues until all of the werewolves have been eliminated, or until the werewolves outnumber the villagers.

You can see why Werewolf raises interesting questions about trust systems. Essentially, the game is about whether or not the villagers can figure out who is lying: who is claiming to be a villager but is actually a werewolf. This creates a lot of stress and theatre. With the right people, it is a lot of fun.

There are, however, a number of interesting lessons that come out of Werewolf that make it a fun tool for thinking about trust, organization and cooperation. And many strategies – including some that are quite ruthless – are quite rational under these conditions. Here are some typical strategies:

1. Kill the Newbies

If you are playing werewolf for the first time and people find out, the village will kill you. For first time players – and I remember this well – it sucked. It felt deeply unfair… but on further analysis it is also rational.

Villagers have only a few rounds to figure out who are the werewolves, and there are strategies and tactics that greatly improve their odds. The less familiar you are with those strategies the more you threaten the group’s ability to defeat the werewolves. This makes the calculus for dealing with newbies easy: at best the group is eliminating a werewolf, at worst they are eliminating someone who hurts the odds of them winning. Hence, they get eliminated.

I’m assuming that similar examples of this behaviour take place when a network gets compromised. Maybe new nodes are cut off quickly, leaving the established nodes to start testing one another to see if they can be trusted. Of course, the variable could be different; a threat could spark a network to kill connections to all connections that, say, have outdated firmware. The point is, that such activities, while sweeping, unfair and likely punishing many “innocent” members, can feel quite rational for those part of the group or network.

2. Noise Can be Helpful

The most important villager is the seer, since they are the only one that can know – with certainty – who is a werewolf and a villager. Their challenge is to communicate this information to other villagers without revealing who they are to the werewolves (who would obviously kill them during the next night).

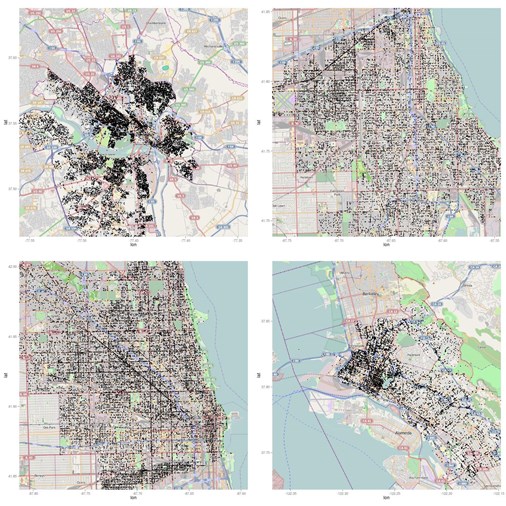

Good seers first ask the facilitator if the person next to them is a villager, then the person to the other side and then slowly moving out (see figure 1 below). If the person next to them is a villager they can then confide in them (e.g. round 1). Good seers can start to build a “chain” of verified villagers (round 2-3) who, as a voting block can protect one another and kill suspected (or better identified) werewolves at the end of each “day.”

This strategy, however, is predicated on the seer being able to safely communicate with those on their left and right. Naturally, werewolves are on the lookout for this behaviour. A player that keeps discreetly talking to those on their left and right makes themselves a pretty obvious target for the werewolves. Thus it is essential during each round that everyone talk to the person to their left and right, regardless of whether they have anything relevant to say or not. Getting everyone talk creates noise that anonymizes communication and interferes with the werewolves’ ability to target the seer.

This is a wonderful example of a simple counter-surveillance tactic. Everybody engages in a behaviour so that it is impossible to find the one person doing it who matters. It was doubly interesting for me as I’ve normally seen noise (e.g. unnecessary communication) as a problem – and rarely as a form of counter-power.

Moreover, in a hostile environment, this form of trust building needs to happen discreetly. The werewolves have the benefit of being both anonymous (hidden) from the villagers but are highly connected (they know who the other werewolves are). The above strategy focuses on destroying the werewolves by using creating a parallel network of villagers who are equally anonymous and highly connected but, over time, greater in number.

3. Structured and Random Stress Tests

The good news for villagers is that many people are terrible liars. Being a werewolf is hard, in part because it is fun. You have knowledge and power. Many people get giddy (literally!). They laugh or smirk or overly compensate by being silent. And some… are liable to say something stupid.

As a result, in the first round players will often insist that everyone introduce themselves and say their role. E.g. “Hi my name is David Eaves and I’m a villager.” You’d be surprised how many people screw up. On rare occasions people will omit their role, or stumble over it, or pause to think about it. This is a surefire way of getting eliminated. It comes back to lesson 1. With poor information, any information that might mean you are a werewolf is probably worth acting on. Werewolf: it’s a harsh, ruthless world.

This may be a interesting example of why ritual and consistency can become prized in a community. It is also a caution about the high transaction costs created by low-trust environments (e.g. ones where you worry the person you are talking to is lying). I’ve heard of (and have experienced first hand) border guards employing a form of the above strategy. This includes yelling at someone and intimidating them to the point where they confess to some error. If a a small transgression is admitted to, this can be used as leverage to gain larger confessions or to simply remove the person from the network (or, say, deny them entry into the country).

However, I suspect this strategy has diminishing returns. People who haven’t screwed up in the first two rounds probably aren’t going to. However, I suspect perpetuating this strategy is something werewolves love. This is because it is an approach that is devoid of fact. Ultimately any minor deviation from an undefined “right” answer becomes justification for eliminating people – thus the werewolves can convince villagers to eliminate people for trivial reasons, and not spend their time looking at who is eliminating who, and who is coming to the aid of who in debate, patterns that are likely more effective at revealing the werewolves.

A note on physical setup

Virtually every time I’ve played werewolf it has been in a room, with the players sitting around a large table. This has meant that a given player can only talk, discreetly, with the player to their left and right. I have once played in a living room where people basically were in an unstructured heap.

What’s interesting is that I suspect that unstructured groups aid the werewolves. The seer strategy outlined in section 2 would be much more difficult to execute in a room where people could roam. A group of people that clustered around a single player would quickly become obvious. There are probably strategies that could be devised to overcome this, but they would probably be more complicated to execute, and so would create further challenges for the villagers.

So perhaps some rigidity to the structure of a community or network can go a long way to making it easier to build trust. This feels right to me, but I’m not sure what more to add on this.

All of this is a simple starting point (I’m sure I have few readers left at this point). But it would be fun to think of more ways that Werewolf could be used as a fun teaching tool around networks, trust and power. Definitely interested in hearing more thoughts.