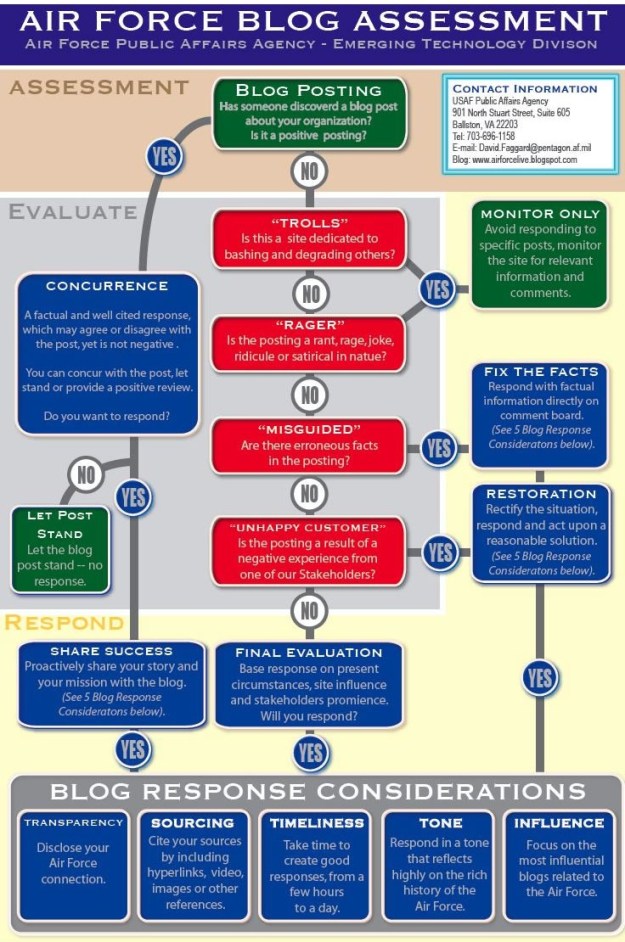

A friend forwarded me this interesting diagram that is allegedly used by the United States Air Force public affairs agency to assess how and if to respond to external blogs and comments that appear upon them.

It’s a fascinating document on many levels – mostly I find it interesting to watch how a command and control driven bureaucracy deals with a networked type environment like the blogosphere.

In the good old days you could funnel all your communications through the public affairs department – mostly because there were so few channels to manage – TV, radio and print media – and really not that many relevant actors in each one. The challenge with new media is that there are both so many new channels emerging (YouTube, twitter, blogs, etc…) that public affairs departments can’t keep up. More importantly, they can’t react in a timely fashion because they often don’t have the relevant knowledge or expertise.

Increasingly, everyone in your organization is going to have to be a public affairs person. Close off your organizations from the world, and you risk becoming irrelevant. Perhaps not a huge problem for the Air Force, but a giant problem for other government ministries (not to mention companies, or the news media – notice how journalists rarely ever respond to comments on their articles…?).

This effort by a bureaucracy to develop a methodology for responding to this new and diverse media environment is an interesting starting point. The effort to separate out legitimate complaints from trolls is probably wise – especially given the sensitive nature of many discussions the Air Force could get drawn into. Of course, it also insulates them from people who are voicing legitimate concerns but will simply be labeled as “a troll.”

Ultimately however, no amount of methodology is going to save an organization from its own people if the underlying values of the organization are problematic. Does your organization encourage people to treat one another with respect, does it empower its employees, does it value and even encourage the raising of differing perspectives, is it at all introspective? Social media is going to expose organizations underlying values to the public, the good, the bad and the ugly. In many instances the picture will not be pretty. Indeed, social media is exposing all of us – as individuals – and revealing just exactly how tolerant and engaging we each are individually. With TV a good methodology could cover that up – with social media, it is less clear that it can. This is one reason why I believe the soft skills are mediation, negotiation and conflict management are so important, and why I feel so lucky to be in that field. Its relevance and important is only just ascending.

Methodologies like that shown above represent interesting first starts. I encourage governments to take a look at it because it is at least saying: pay attention to this stuff, it matters! But figuring out how to engage with the world, and with people, is going to take more than just a decision tree. We are all about to see one another for what we really are – a little introspection, and value check, might be in order…