Last week was a bad week for the government on the copyright front. The government recently tabled legislation to reform copyright and the man in charge of the file, Heritage Minister James Moore, gave a speech at the International Chamber of Commerce in which he decried those who questioned the bill as “radical extremists.” The comment was a none-too-veiled attack at people like University of Ottawa Professor Michael Geist who have championed for reasonable copyright reform and who, like many Canadians, are concerned about some aspects of the proposed bill.

Unfortunately for the Minister, things got worse from there.

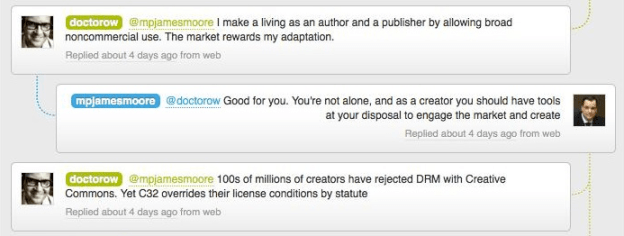

First, the Minister denied making the comment in messages to two different individuals who inquired about it:

Still worse, the Minister got into a online debate with Cory Doctorow, a bestselling writer (he won the Ontario White Pine Award for best book last year and his current novel For the Win is on the Canadian bestseller lists) and the type of person whose interests the Heritage Minister is supposed to engage and advocate on behalf of, not get into fights with.

In a confusing 140 character back and forth that lasted a few minutes, the minister oddly defended Apple and insulted Google (I’ve captured the whole debate here thanks to the excellent people at bettween). But unnoticed in the debate is an astonishing fact: the Minister seems unaware of both the task at hand and the implications of the legislation.

The following innocuous tweet summed up his position:

Indeed, in the Minister’s 22 tweets in the conversation he uses the term “market forces” six times and the theme of “letting the market or consumers decide” is in over half his tweets.

I too believe that consumers should choose what they want. But if the Minister were a true free market advocate he wouldn’t believe in copyright reform. Indeed, he wouldn’t believe in copyright at all. In a true free market, there’d be no copyright legislation because the market would decide how to deal with intellectual property.

Copyright law exists in order to regulate and shape a market because we don’t think market forces work. In short, the Minister’s legislation is creating the marketplace. Normally I would celebrate his claims of being in favour of “letting consumers decide” since this legislation will determine what these choices will and won’t be. However, the Twitter debate should leave Canadians concerned since this legislation limits consumer choices long before products reach the shelves.

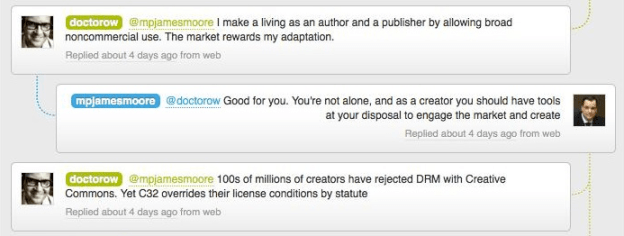

Indeed, as Doctorow points out, the proposed legislation actually kills concepts created by the marketplace – like Creative Commons – that give creators control over how their works can be shared and re-used:

But advocates like Cory Doctorow and Michael Geist aren’t just concerned about the Minister’s internal contradictions in defending his own legislation. They have practical concerns that the bill narrows the choice for both consumers and creators.

Specifically, they are concerned with the legislation’s handling of what are called “digital locks.” Digital locks are software embedded into a DVD of your favourite movie or a music file you buy from iTunes that prevents you from making a copy. Previously it was legal for you to make a backup copy of your favourite tape or CD, but with a digital lock, this not only becomes practically more difficult, it becomes illegal.

Cory Doctorow outlines his concerns with digital locks in this excellent blog post:

They [digital locks] transfer power to technology firms at the expense of copyright holders. The proposed Canadian rules on digital locks mirror the US version in that they ban breaking a digital lock for virtually any reason. So even if you’re trying to do something legal (say, ripping a CD to put it on your MP3 player), you’re still on the wrong side of the law if you break a digital lock to do it.

But it gets worse. Digital locks don’t just harm content consumers (the very people people Minister Moore says he is trying to provide with “choice”); they harm content creators even more:

Here’s what that means for creators: if Apple, or Microsoft, or Google, or TiVo, or any other tech company happens to sell my works with a digital lock, only they can give you permission to take the digital lock off. The person who created the work and the company that published it have no say in the matter.

So that’s Minister Moore’s version of “author’s rights” — any tech company that happens to load my books on their device or in their software ends up usurping my copyrights. I may have written the book, sweated over it, poured my heart into it — but all my rights are as nothing alongside the rights that Apple, Microsoft, Sony and the other DRM tech-giants get merely by assembling some electronics in a Chinese sweatshop.

That’s the “creativity” that the new Canadian copyright law rewards: writing an ebook reader, designing a tablet, building a phone. Those “creators” get more say in the destiny of Canadian artists’ copyrights than the artists themselves.

In short, the digital lock provisions reward neither consumers nor creators. Instead, they give the greatest rights and rewards to the one group of people in the equation whose rights are least important: distributors.

That a Heritage Minister doesn’t understand this is troubling. That he would accuse those who seek to point out this fact and raise awareness to it as “radical extremists” is scandalous. Canadians have entrusted in this person the responsibility for creating a marketplace that rewards creativity, content creation and innovation while protecting the rights of consumers. At the moment, we have a minister who shuts out the very two groups he claims to protect while wrapping himself in a false cloak of the “free market.” It is an ominous start for the debate over copyright reform and the minister has only himself to blame.

In a month where our federal government cited imaginary data to justify policies on crime and has eliminated the gathering a huge swaths of effective data necessary for the efficient governing of our cities and rural communities as well as ensuring critical services will no longer reach innumerable Canadians, it is nice to see a province trying to do the opposite: not only understand that effective data is the cornerstone to good policy but to enable everyday, ordinary Canadians to leverage it so as to make smarter decisions, influence policy debates and empower themselves. It’s what a modern democracy, economy and civil society should look like.

In a month where our federal government cited imaginary data to justify policies on crime and has eliminated the gathering a huge swaths of effective data necessary for the efficient governing of our cities and rural communities as well as ensuring critical services will no longer reach innumerable Canadians, it is nice to see a province trying to do the opposite: not only understand that effective data is the cornerstone to good policy but to enable everyday, ordinary Canadians to leverage it so as to make smarter decisions, influence policy debates and empower themselves. It’s what a modern democracy, economy and civil society should look like.